1.

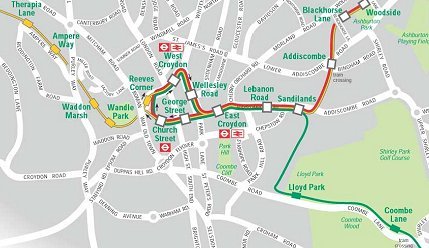

Croydon

(Tramlink),

or back to: [intro] [menu]

London

has two light rail systems in addition to the Underground and

suburban rail services. These are the Docklands Light Railway

(DLR) and Croydon Tramlink. Both systems have connections to the

Underground and to suburban rail services. Croydon Tramlink is

fed by bus routes serving housing estates in and around New Addington,

an area which had limited access to public transport before the

system opened. Where possible, bus and tram stops are placed close

together, with step-free access between them.

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Croydon, centre, February 14, 2002

"Because Trams Beat Jams!"

"Because Trams Beat Jams!"

In

July 1998, John Prescott stated in a Government White paper that:

'In a major consultation exercise, people made clear that the

time for action is long overdue. People want more choice, more

alternatives to using their cars and more reliable journeys when

they do drive. They want a better public transport system that

doesn't let them down. They want better protection for the environment,

and they want less pollution because they are worried about their

health.'

Tramlink meets the criteria stated in the White Paper.

It provides a real alternative to the private car, reduces pollution,

improves journeys for thousands of people everyday and contributes

to the economic well being of the area it serves.

Less

is More

Tramlink's electrically powered trams are energy and space efficient.

In fact a 30 metre tram (the length of 6 cars) can carry up to

200 people, and that's nearly 3 times as many as a double decker

bus.

A double tram track has more capacity than a dual carriageway,

yet requires only one third of the space. Trams use far less fuel

per passenger than cars, taxis, and other road vehicles, and do

not emit any fumes.

Overhead

Power

Tramlink is much less intrusive than conventional railways as

it does not need wide sections of segregated track. Our trams

can also climb steeper gradients and handle tighter curves, thereby

fitting in around existing buildings and spaces. Long stretches

of our routes use converted railway tracks which are no longer

in use, minimising visual and noise impact.

Noise

Impact

One of the outstanding features of Tramlink is the quiet and smooth

running of the trams. Powered by electricity wires overhead, modern

trams generate none of the engine noise of cars, lorries or other

road vehicles. In fact Tramlink has been designed with noise reduction

in mind. In order to minimise noise, wheels are lubricated to

reduce squeaking and track is continuously welded and mainly set

in ballast. At our depot all practical steps have been taken in

accordance with the 1990 Environmental Pollution Act.

Air

Quality

Existing modes of transport are significant sources of air pollution.

Exhaust fumes are thought to cause harm to health particularly

to those already suffering from respiratory illnesses. Motor vehicle

gases also contribute to global warming - about half the current

warming effect is due to carbon dioxide (CO2). The Croydon Environment

Audit 1995 estimated that nearly 880,000 tonnes of CO2 are emitted

by vehicles in the Croydon area every year. Although the generation

of electricity needed to run trams has the potential to create

air pollution from the power station, this is subject to strict

government controls and trams do not emit fumes or pollutants.

Photo: (C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Croydon, TramTrain

interchange, Beckenham, February

14, 2002

Flora

& Fauna

In building the Tramlink system, we have kept to a minimum the

need to disrupt wildlife. Where trees absolutely had to be removed

then replacement planting forms part of the landscaping works.

When this landscaping is complete there will be more trees in

the area than there were prior to construction. Croydon Council

has responsibility for landscaping, for which it has set aside

a million pounds, and is undertaking a comprehensive programme

of replanting which ensures high standards are met.

Soil

& Architectural Surveys

Any soil brought into the Addington Hills area is similar to existing

soil to ensure that 'alien' material is not imported. The opportunity

is being taken to re-establish areas of heather which have been

smothered by recent tree growth. Wessex Archaeology carried out

an Archaeological Impact Study to identify and protect all known

or suspected remains along the routes - archaeological investigations

took place during construction in certain areas.

Badgers

Discussions were held with wildlife groups and the Joseph Firbank

Society on the most appropriate ways of protecting badgers living

along the route. Badger tunnels and badger proof fences will ensure

that badgers cross safely and with ease.

Creating new open space

Creating new open space

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Croydon, Coombe Lane, February 14, 2002

Croydon

Council has established 2 new open spaces to replace land used

by Tramlink:

Stroud Green Well in Shirley. This 5 acre site was once a playing

field but had become overgrown. It has now been cleared and opened

to the public.

Threehalfpenny Wood. 6 acres previously known as Addington Soakage

Field has been transformed and opened to the public.

Network

Network

Three

lines cover the conurbation of Southern London:

1 - to Wimbledon

in the west, and a branche tot the northeast

1 - to Wimbledon

in the west, and a branche tot the northeast

2 - to Beckham

(northeast)

2 - to Beckham

(northeast)

3- to housing

area New Addington (southeast)

3- to housing

area New Addington (southeast)

All lines use the single loop in the centre of Croydon.

Data

Data

Opened in

May 2000. Cost of construction: £200 million. Tramlink operates

in and around Croydon, south London. Line 1 runs between Wimbledon

in the south west, where it connects to London Underground, via

a loop in central Croydon, to Elmers End in the east, with connections

to suburban rail services. Line 2 links central Croydon with suburban

rail services in Beckenham. Line 3 serves New Addington in the

south east. Feeder buses provide further links in the area.

Opened in

May 2000. Cost of construction: £200 million. Tramlink operates

in and around Croydon, south London. Line 1 runs between Wimbledon

in the south west, where it connects to London Underground, via

a loop in central Croydon, to Elmers End in the east, with connections

to suburban rail services. Line 2 links central Croydon with suburban

rail services in Beckenham. Line 3 serves New Addington in the

south east. Feeder buses provide further links in the area.

Operator:

Tramtrack Croydon / FirstGroup.

Operator:

Tramtrack Croydon / FirstGroup.

Number of

stations: 38, all wheelchair accessible. Step-free access to low

platforms and the adjacent streets.

Number of

stations: 38, all wheelchair accessible. Step-free access to low

platforms and the adjacent streets.

Length of

Route: 28 km, 3 lines.

Length of

Route: 28 km, 3 lines.

Staff: 181

Staff: 181

Fleet: 24

trams, all wheelchair accessible.

Fleet: 24

trams, all wheelchair accessible.

·

Power supply: 750V DC overhead line.

·

Power supply: 750V DC overhead line.

Partly segregated,

with on-street running in Croydon. Many ungated level crossings

of roads and footpaths. No track or signal sharing with other

railways. Trams use their own platforms in Wimbledon and Elmers

End stations.

Partly segregated,

with on-street running in Croydon. Many ungated level crossings

of roads and footpaths. No track or signal sharing with other

railways. Trams use their own platforms in Wimbledon and Elmers

End stations.

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 96 million.

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 96 million.

Passenger

journeys 2000/01: 15 million.

Passenger

journeys 2000/01: 15 million.

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £12.2 million.

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £12.2 million.

Future expansion:

possible extensions to Crystal Palace via Penge or Anerley, and

to Sutton via Morden, subject to feasibility studies and funding.

Future expansion:

possible extensions to Crystal Palace via Penge or Anerley, and

to Sutton via Morden, subject to feasibility studies and funding.

2.

Docklands

(DLR),

or back to: [intro] [menu]

London

has two light rail systems in addition to the Underground and

suburban rail services. These are the Docklands Light Railway

(DLR) and Croydon Tramlink. Both systems have connections to the

Underground and to suburban rail services.

"Will move into profit"

"Will move into profit"

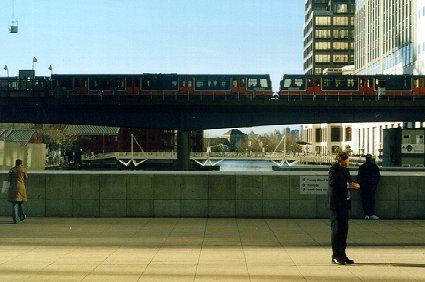

Docklands

light railway (DLR) is of particular interest as it combined elements

of infrastructure funding from increasing land values and profits

from subsequent land sales through a quasi-public holding agency

(London Docklands Development Corporation/LDDC), which was also

temporarily responsible for building and operating the light railway.

Photo: (C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

London, Greenwhich, February 14, 2002

After

planners had initially regarded improved bus services as sufficient

for the amount of additional uses envisioned for the Docklands,

it was soon realised that a fixed-track system would not only

provide much better service quality, but also be a powerful demonstration

to private developers that the government was taking the regeneration

program seriously, thus capable of kick-starting the process (Collins

1990, Schabas 1990). The initial 12-km segment linking Tower Gateway,

Stratford and Island Gardens was funded at equal parts by LT and

LDDC, contracted out in a turnkey arrangement and was built for

only A $ 26.8m per km (1998 values), the lowest figure for completely

grade-separated alignments (see.

While an early parliamentary vote assured half the capital cost

for the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) to be covered by central

government, and commitments of developers could be gained towards

upgrading and extensions in later stages (most notably a £67m

contribution by the now-bankrupt main investor on Canary Wharf,

Olympia and York), the railway soon ran into capacity limits as

well as technical difficulties with automated operation. Costly

replacement of control and signalling systems, which constrained

operations over a 3-year period, as well as additional engineering

tasks like extending platform lengths and inserting level-free

track crossings at route junctions stepped up capital costs which

now stand at more than A $ 110m per km, including two extensions

totalling 9.5 km. Poor reliability and the necessity to suspend

evening and weekend services for the upgrading work had gnawed

at DLR's public image and made its cost recovery ratio plummet

to a low of 15% when the railway was transferred from the responsibility

of London Transport (LT) to LDDC in early 1992.

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

London, Docklands, February 14, 2002

Since

that year, patronage has grown threefold following DLR's upgrading

and extensions and the ongoing intensification of urban activity

in the Docklands area. Cost recovery, too, has improved to over

80% in 1998 (Hope 1999), not least assisted by unconventional

means like hiring out under-used workshop facilities to private

clients. The extension to Beckton, opened in 1994, was made to

prove that it could, over time, be funded from land value increases

in this then largely obsolete corridor (Collins 1990) - a task

facilitated by the fact that LDDC was both the serviced area's

largest landowner and the light rail investor, which eliminated

the need for complicated taxing schemes or lengthy negotiations

with private landowners on funding contributions. Eventually,

DLR's service to Beckton started before redevelopment did, thus

representing a strong incentive to transit-oriented revitalisation.

A further extension of the network to Greenwich and Lewisham,

including an underground Thames crossing, has been contracted

to a private consortium in a 25-year concession to fund, design,

build and maintain, so DLR operates the route on a leaseback basis.

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

London, Docklands, Jubilee Line, February 14, 2002

There

are reasonable expectations that DLR's operation might move into

profit once this crucial link will be in service for some time.

Simultaneously, the Jubilee Line underground extension to Canary

Wharf, as a result of an earlier government decision to improve

access to this largest urban redevelopment area in Europe, is

opened already.

While it had earlier been regarded as a potentially threatening

competition to DLR, after the tremendous increases in ridership

there is now widespread consensus among operators and policymakers

that it brings much-needed relief from DLR's overcongestion and

assist both systems to coordinate to mutual advantage.

Data

Data

Opened in

1987, at an initial cost of £77 million. Since the original

opening, three line extension projects have been carried out:

to Bank (1991, £294m), connecting to London Underground,

to Beckton (1994, £280m), to Lewisham (1999, £250m),

connecting to Connex Rail services. DLR now links Canary Wharf

with the City of London, east and south east London.

Opened in

1987, at an initial cost of £77 million. Since the original

opening, three line extension projects have been carried out:

to Bank (1991, £294m), connecting to London Underground,

to Beckton (1994, £280m), to Lewisham (1999, £250m),

connecting to Connex Rail services. DLR now links Canary Wharf

with the City of London, east and south east London.

Operator:

Serco Docklands Ltd / CGL Rail.

Operator:

Serco Docklands Ltd / CGL Rail.

Number of

stations: 34, all accessible to wheelchairs, generally by lifts.

Number of

stations: 34, all accessible to wheelchairs, generally by lifts.

Length of

route: 27 km, much of it on viaducts.

Length of

route: 27 km, much of it on viaducts.

Staff: 370

Staff: 370

Fleet: 70

passenger cars, all wheelchair accessible.

Fleet: 70

passenger cars, all wheelchair accessible.

Power supply

750V DC side rail.

Power supply

750V DC side rail.

Fully segregated

elevated metro style system.

Fully segregated

elevated metro style system.

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 200.1 million.

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 200.1 million.

Passenger

journeys 2000/01: 38 million.

Passenger

journeys 2000/01: 38 million.

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £29 million.

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £29 million.

Future expansion:

a new line to serve London City Airport. Subject to granting of

powers, construction is due to start early in 2002, due to open

in 2004-5.

Future expansion:

a new line to serve London City Airport. Subject to granting of

powers, construction is due to start early in 2002, due to open

in 2004-5.

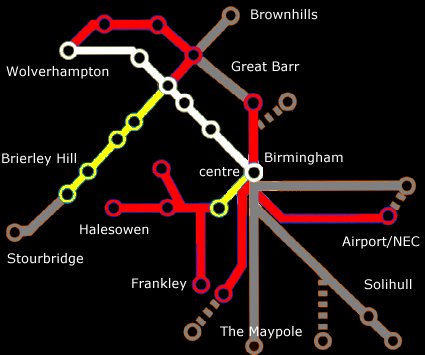

3.

Birmingham/Wolverhampton,

or back to: [intro] [menu]

New Light Rail in the West Midlands

New Light Rail in the West Midlands

Promoted

by Centro and the West Midlands Passenger Transport Authority,

the £145 million Midland Metro opened in the summer of 1999,

it is the first street tramway to run in the West Midlands for

over fourty years. Funding for the project was gathered from various

sources.

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

West Midlands, Wolverhampton, March 14, 2002

The Government gave a £40 million grant and a £40

million approved loan towards the project. £31 million came

from a European grant, £17.1 million from the West Midlands

Passenger Transport Authority, £11.4 million from the private

consortium ALTRAM (who were chosen to design, construct, operate

and maintain the system). £4 million came from Birmingham,

Sandwell and Wolverhampton Councils in conjunction with the Black

Country Development Corporation, £1 million from Centro

and £0.3 million from utility services.

ALTRAM is the consortium running the show, having won a 23 year

concession to operate the system. The ALTRAM team has been responsible

for the construction, design and operation of Midland Metro Line

1. Travel West Midlands was awarded the management contract to

operate Line 1 and a separate division, Travel Midland Metro,

was specially formed to operate and maintain the new Light Rail

System. Travel Midland Metro Head Quarters based in Wednesbury

has been imaginatively named the METRO CENTRE (not to be confused

with the giant North East shopping mall!)

John Laing plc, constructors of Birmingham International Airport's

Eurohub terminal, were responsible for the construction of the

track, stops and buildings. Ansaldo Trasporti, the Italian-based

rail and signalling supplier, were responsible for delivering

the trams, signalling and communications equipment, overhead line

equipment and power suplly.

Privatisation and PFI Deals in the

West Midlands

Privatisation and PFI Deals in the

West Midlands

Source:

Labour Research Department for the GMB (October 2001)

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

West Midlands, Birmingham/centre, March 14, 2002

Introduction

of a report which looks at how far public services in the West

Midlands Area have been transferred to the private sector.

The

report finds that the private sector is now getting more than

£200 million a year from operating public services in the

area. This does not include the income from two major transport

schemes, the Midland Metro Line 1 and the motorway alternative

to the M6 between junctions 4 and 11.

It identifies a total of 119 separate contracts from 26 separate

public authorities, ranging from the housing repairs to urban

planning services to the provision of catering services.

By far the biggest is the £50 million per year repairs and

maintenance contract that Birmingham City Council gave Serviceteam

in April this year. Together with the £25 million contract

given to Accord at the same time, this means that repairs and

maintenance for

88,000 council properties are in the hands of these two contractors

for the next five years.

This is not Serviceteam's only contract with Birmingham City Council.

It also has a £5m grounds maintenance contract running for

10 years. Other companies with more than one contract in the West

Midlands include: Compass Group plc, which owns Chartwells and

Sutcliffe Catering (UK), has four contracts in the area; We Are

Cleaning (GB) has contracts with three authorities and Brophy

plc has two separate contracts with Wolverhampton Council. Onyx

has contracts with Birmingham City Council and Walsall Hospitals

NHS Trust, with the Birmingham City contract worth £25 million

a year.

Not all the authorities have provided details on the value of

the services carried out by the private sector (see below), but

using figures from those who have, it can be estimated that in

the West Midlands area these authorities pay some £140 million

a year to the private sector to deliver contracted-out services.

In addition, local bodies have signed 9 PFI deals in the West

Midlands area, and more are planned. In total these have a capital

value of £293 million. On average most larger, long-term

PFI schemes involve payments of between 20% and 25% of the capital

value per year. (The percentage is higher for shorter more capital

intensive schemes, like IT). This means that through the 9 PFI

schemes in the West Midlands area an estimated further £66

million is being paid to the private sector to deliver public

services.

PFI schemes have been signed by local councils, local health authorities

and central government departments: deals include the refurbishment

of 10 Birmingham schools; the provision of a new hospital radiology

department, and two waste to energy contracts.

Furthermore, there are 2 PFI deals in the West Midlands Area with

a capital value of £595 million in the transport sector.

These are the Midland Metro Line 1 and the new toll alternative

to the M6 between junctions 4 and 11. The precise value to the

contractors involved, is difficult to calculate as it depends

on usage but the companies involved can count on retums over a

long period, 20 years after construction for the Midland Metro

Line 1 and 50 years for the motorway.

Network

Network

Phasing

of the Midland Metro network development (from the Highh Volume

Corridors Study of consultant Steer Davies Gleave (2001):

Phase 1 -

Extensions to the excisting line (Birmingham-Wolverhampton). Two

branches: from Wednesbury to Brierly, and in Birningham from Snow

Hill (current terminus) to the city centre.

Phase 1 -

Extensions to the excisting line (Birmingham-Wolverhampton). Two

branches: from Wednesbury to Brierly, and in Birningham from Snow

Hill (current terminus) to the city centre.

Phase 2 -

three new routes, from Great Barr through Birmingham city centre

to Bournbrook, from Airport/Nec, again throught Birmingham centre

to Oldbury, Halesowen and Frankley, and from Wolverhampton to

Walsall.

Phase 2 -

three new routes, from Great Barr through Birmingham city centre

to Bournbrook, from Airport/Nec, again throught Birmingham centre

to Oldbury, Halesowen and Frankley, and from Wolverhampton to

Walsall.

Phase 3-

Many options possible. All programmed to open in 2012.

Phase 3-

Many options possible. All programmed to open in 2012.

Data

Data

Opened: 1999;

Cost of construction: £145 million. Line 1 of a proposed

three line system, with a mixture of on-street and segregated

running on new formations.

Opened: 1999;

Cost of construction: £145 million. Line 1 of a proposed

three line system, with a mixture of on-street and segregated

running on new formations.

Operator:

Altram consortium.

Operator:

Altram consortium.

Number of

stations: 23, wheelchair accessible. Step-free access to low platforms

and streets.

Number of

stations: 23, wheelchair accessible. Step-free access to low platforms

and streets.

Length of

route: 20 km

Length of

route: 20 km

Staff: 144

Staff: 144

Fleet: 16

passenger cars, all wheelchair accessible.

Fleet: 16

passenger cars, all wheelchair accessible.

Power supply:

750V DC overhead line.

Power supply:

750V DC overhead line.

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 55.8 million

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 55.8 million

Passenger

journeys 2000/01: 5.4 million

Passenger

journeys 2000/01: 5.4 million

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £3.1 million

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £3.1 million

Future expansion:

proposed extensions further into central Birmingham and to Merry

Hill.

Future expansion:

proposed extensions further into central Birmingham and to Merry

Hill.

4.

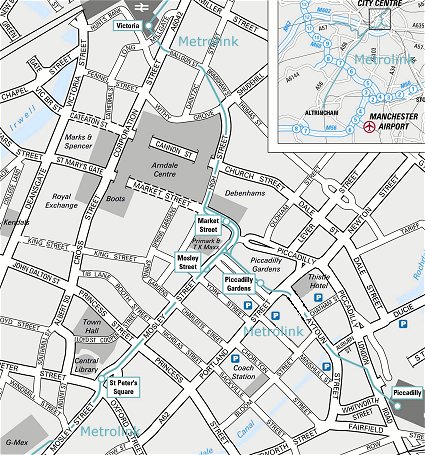

Manchester

(Metrolink) ,

or back to: [intro] [menu]

The best Light Rail system in the world?

The best Light Rail system in the world?

by Pete

Black (Light Rail Planning Officer, GMPTE)

Metrolink

has become such a part of Greater Manchester that if you buy a

postcard, the chances are that it will have a tram on it. At peak

times trams are crowded with people who used to commute by car

and off-peak it is well used by everyone. Metrolink has brought

an unprecedented level of mobility to many groups and has even

created new markets for public transport. So how and why is Metrolink

successful, and what new developments are there?

Photo: (C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Manchester, G-MEX, February, 13, 2002

How

did it all start?

Metrolink opened in 1992 at a cost of around £152 million.

A design, build, operate and maintain (for fifteen years) contract

refurbished two run-down suburban rail lines and linked them by

a short section of track across Manchester City Centre with a

spur to Piccadilly, the main rail station. A fleet of 26 trams

operate a service every six minutes for most of the day between

Bury to the north of Manchester and Altrincham to the Southwest

over the 31km network.

Metrolink has now reached 13.9 million passengers a year and rising

after six years of operation. This compares to the forecast maximum

patronage of 12 million, and the 7.5 million annual trips made

on the two heavy rail lines before conversion to Metrolink. Detailed

monitoring studies have revealed that 65% of Metrolink passengers

have a car which they could have used instead of Metrolink and

that within the prime target area (within 2km of the line) between

14% and 50% of car trips to destinations served by Metrolink have

switched to Metrolink. These alone are stunning successes in a

conurbation with cheap and often free car parking for commuters

and little car restraint. Even better are the benefits that come

from full wheelchair accessibility to many other groups such as

parents with pushchairs or older people. Some completely new public

transport markets have appeared such as short trips within the

city centre, and journeys within the corridor rather than to the

major centres of Manchester, Bury and Altrincham.

Why

is it so successful?

It is not hard to see reasons for the success of Metrolink. The

system is simple and easily understood. Segregated suburban running

means quick journeys, and city centre track gives good access

to the main attractions and work places. The service is frequent

and reliable.

Most importantly the system is safe to travel on, and safe to

get to - stops and car parks have CCTV surveillance and "panic

buttons". The main problem seems to be the need for extra

capacity in the peak hours. Extra capacity would almost certainly

take more cars off the road.

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Manchester, Eccles, February, 13, 2002

Where

are we up to?

Extensions were planned even before the first tram ran and if

they were all built would triple the network. Following the financial

and transport success of the first lines construction of the first

extension through Salford Quays to Eccles is now underway. A new

contract to design and build the ?160 million extension and to

operate the expanded network including the existing system was

put out to tender and was awarded to Altram. Altram is a consortium

of Laing (Civil Engineers), Ansaldo (Italian tram manufacturer),

Serco (operator), and 3i (venture capital company). The new line

will be very different from the existing system. The first section

threads through Salford Quays, a Docklands regeneration area.

Development has been patchy up to now due to poor access, but

Metrolink is likely to lead a building boom. The second section

is street running along Eccles New Road. This will serve a significant

residential population, a large park and ride site and the centre

of Eccles. The line is expected to open in Spring 2000.

Powers already exist for four further extensions to Oldham and

Rochdale (24 km), Manchester Airport (21 km), the Trafford Centre

(7 km) and East Didsbury (5 km). Greater Manchester Passenger

Transport Authority's top priority is now the scheme to take over

the Railtrack "Oldham Loop" line which will involve

new street running sections to serve the centres of Oldham and

Rochdale. This extension could carry eight million passengers

each year. The Airport Extension was approved by the Government

in 1997. As well as the huge potential for passenger and staff

journeys the line would serve Wythenshawe Hospital and a large

residential population in the south of the city. Powers also exist

to build Metrolink to the out-of-town Trafford Centre but the

Authority believes this line should be funded entirely by the

private sector. Compulsory purchase powers are currently being

renewed for this extension. Compulsory purchase powers are also

being renewed for an extension to East Didsbury. This line is

unlikely to be built as a complete extension but the potential

exists to extend the line to GMPTE is also awaiting the outcome

of a public inquiry held in June 1997 into proposals to extend

Metrolink 10km to Ashton-under-Lyne, serving a large residential

population, Ashton town centre and several major regeneration

areas including the Commonwealth Games site which will have a

new stadium.

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Manchester, centre, February, 13, 2002

Conclusion

In just six years Metrolink has established itself as a very successful

transport system. It has increased mobility for many groups while

tempting people out of their cars. It has been able to do this

in a deregulated bus environment, with little or no traffic restraint

and without operating subsidy. It is an indispensable part of

any integrated transport strategy for Manchester.

The success of Metrolink may be partly to do with the size and

density of Greater Manchester, and the specific route. Light Rail

is an expensive option which can only currently be justified for

large cities. But it is a very impressive record, and a clear

indication that investment in good quality public transport works.

Come and see for yourselves!

Network

Network

Data

Data

Opened: 1992

at an initial cost of construction of £140 million. A two

line system with both sections meeting on-street in central Manchester

in Piccadily Gardens. Extension to Eccles opened in March 2000,

£160 million.

Opened: 1992

at an initial cost of construction of £140 million. A two

line system with both sections meeting on-street in central Manchester

in Piccadily Gardens. Extension to Eccles opened in March 2000,

£160 million.

Operator:

Altram.

Operator:

Altram.

Number of

stations: 36. Standard height platforms as many suburban stations

are served by the system.

Number of

stations: 36. Standard height platforms as many suburban stations

are served by the system.

Length of

route: 39.1 km

Length of

route: 39.1 km

Staff: 303

Staff: 303

Fleet: 32

passenger carriages, high floor design similar to trains, but

wheelchair accessible.

Fleet: 32

passenger carriages, high floor design similar to trains, but

wheelchair accessible.

Power supply

750V DC overhead line.

Power supply

750V DC overhead line.

Partly segregated.

Major use of former rail alignments, with street running in central

Manchester. Metrolink shares major stations with rail franchise

holders.

Partly segregated.

Major use of former rail alignments, with street running in central

Manchester. Metrolink shares major stations with rail franchise

holders.

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 152.3 million

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 152.3 million

Passenger

journeys 2000/01:17.2 million

Passenger

journeys 2000/01:17.2 million

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £18 million

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £18 million

Future expansion:

three extensions approved using a mixture of street running, former

railway alignments and some new alignments. One line will serve

Manchester Airport.

Future expansion:

three extensions approved using a mixture of street running, former

railway alignments and some new alignments. One line will serve

Manchester Airport.

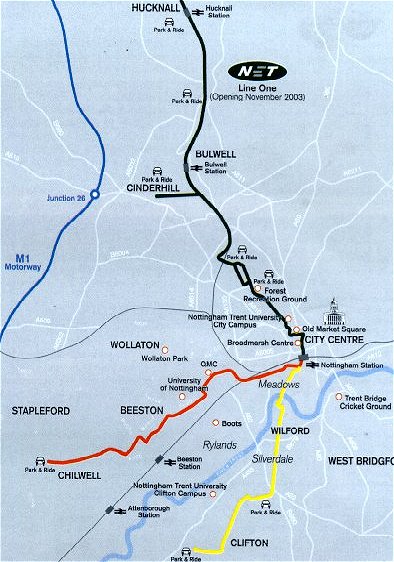

5.

Nottingham

(NET),

or back to: [intro] [menu]

The first tram is unveiled at Bombardier's works in Derby on 13

August by Transport Minister John Spellar.

Photo courtesy: LRTA

Nottingham

needed an integrated transport system

Nottingham

needed an integrated transport system

The

new tramway of Nottingham (UK) - Nottingham Express Transit line

1 - has been launched March 8th (2004) by Alistair Darling, the

Secretary of State for Transport. It took sixteen years of planning

and more than three years of construction to make this Grenoble

inspired tramway a reality. NET is a state-of-the-art tram system,

which is successful already. It runs from Hucknall, through Bulwell

and Hyson Green and into the city centre, terminating at Nottingham

railway station. There is also a spur line to Phoenix Park (just

off the M1 at junction 26).

Some

history... Back in 1988 Nottingham City Council and Nottinghamshire

County Council came together with Nottingham Development Enterprise

, representing local businesses interest, to consider the city's

future transport needs. It was clear that if Nottingham's fabric

and economy were to be regenerated and the Nottingham of the future

was to be a city that remained a great place to live, work and

visit then our transport infrastructure had to be renewed.

The overriding principle of these considerations was that Nottingham

needed an integrated transport system and that high quality, reliable

public transport had to form the backbone of that system. Nottingham

needed a public transport system that could move large numbers

of people without contributing the problems we needed to solve;

road congestion and local pollution. A number of options were

considered before a light rail vehicle, a tram, was decided upon

as Nottingham's solution. Powered by electricity, well-suited

to integration with the city's traffic management systems, clearly

of a high quality and economically feasible to build and to run

Nottingham's tram would form the ideal backbone to the public

transport system of the Nottingham of the future.

During 1994 working through the GNRT company, the two Council's

presented to Parliament their plans for the first line of a tram

system running from Hucknall, in the former coalfields to the

north of Nottingham, right through to the heart of the cityand

with a spur line to Cinderhill and attract motorists onto public

transport with ample park and ride facilities all along its route.

Lengthy deliberations in committees of the House of Commons and

House of Lords and the submission of extensive evidence covering

viability, public acceptability and environmental impact ended

with the granting, subject to a number of Undertakings on the

part of the two Councils, of permission to build Nottingham's

tram in the GNLRT Act 1994.

Tram systems are not cheap to build - but they are worth it. All

utility services must be moved from under the tram route before

tracks can be laid and overhead power lines installed. New bridges

must be built and new road layouts are needed. You need a fleet

of trams and depot in which to house and maintain them. All in

all a £200 million investment.

The two Council's invited tenders to build their tram system and

selected Arrow Light-Rail from a strong field as their chosen

concession company to design, build and operate Nottingham's tram.

Arrow Light-Rail comprises civil engineering firm Carillion ,

rail vehicle builder Bombardier (formerly ADtranz), experienced

integrated public transport operator Transdev and, importantly,

Nottingham City Transport the largest existing public transport

provider in the city.

Arrow's funding to build the tram is secured via a Private Finance

Initiative for which Government approved credit in December 1998.

Once this PFI funding was confirmed detailed negotiations were

embarked upon, in May 2000 contracts were signed and in June 2000

work to build a public transport system fit for the Nottingham

of the future began.

The NET Project Team, working for both Councils and based in Nottingham

City Council's Lawrence House offices, now acts as client for

the project ensuring that what Nottingham gets from Arrow is the

best system possible and the impact of construction on the vibrant

life of the city is minimised. The team is also managing the consideration

of future route options aiming to start work on more lines by

the time line one is complete. (2002)

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Nottingham, city centre, May 27, 2004

Design,

build, fund, operate and maintain

Design,

build, fund, operate and maintain

Arrow

Light Rail Ltd is a special purpose company formed to design,

build, fund, operate and maintain Line One of Nottingham Express

Transit (NET), a modern light rail tram system for Nottingham.

Arrow is owned by six partners, each bringing their own particular

skill and expertise to the organisation:

The Promoters of the scheme, jointly Nottingham City Council and

Nottinghamshire County Council, awarded the concession to Arrow

for a period of 30.5 years, under what is the largest local authority

Private Finance deal ever completed.

Arrow have let a 3.5 years fixed price turnkey contract to a consortium

comprising Adtranz and Carillion Construction for the design and

construction of the tram system. Adtranz are providing the trams,

power, signalling and communications systems, and Carillion the

civil engineering, track and tramstops.

Arrow has also let a contract to the Nottingham Tram Consortium

(NTC), comprising Transdev and Nottingham City Transport, who

will operate and maintain the system for 27 years.

Network

Network

Line

1 runs from Hucknall, north of the city, into the centre of Nottingham

and its railway station. A park-and-ride site close to the M1

will be connected with Nottingham via a spur at Cinderhill.

A consultant team led by Turner & Townsend and officers of

the councils have developed proposals for expansion of the system

(mid 2002). They recommended routes for line 2 (Clifton via Wilford)

and line 3 (Beeston and Chilwell via Queens Medical Centre).

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Remained tracks of Nottingham's 'Victorian' tramway (closed 1936);

at bus depot (former tramway depot)

Nottingham, September 13, 2002

Data

Data

Opening:

March 2004. Cost of construction: £180 million (PFI).

Opening:

March 2004. Cost of construction: £180 million (PFI).

Operator:

Arrow.

Operator:

Arrow.

Number of

stations: 23 (including 5 P&R sites). Low platforms.

Number of

stations: 23 (including 5 P&R sites). Low platforms.

Length of

route: 14 km

Length of

route: 14 km

Staff: ...

Staff: ...

Fleet: 15

passenger carriages (Bombardier), 100% low floor, 33 m long.

Fleet: 15

passenger carriages (Bombardier), 100% low floor, 33 m long.

Power supply

750V DC overhead line.

Power supply

750V DC overhead line.

Partly segregated.

Major use of former rail alignments (no track sharing), with street

running in central Nottingham.

Partly segregated.

Major use of former rail alignments (no track sharing), with street

running in central Nottingham.

Future expansion:

two extensions planned (Line 2 and 3).

Future expansion:

two extensions planned (Line 2 and 3).

6.

Newcastle,

or back to: [intro] [menu]

The Tyne and Wear Metro

The Tyne and Wear Metro

Track

sharing at East Boldon

On the 'main line' from Pelaw to Sunderland

Photo courtesy: LRTA

Newcastle

(300,000 inhabitants) is the centre of Tyne and-Wear, an urban

region (> 1,000,000 inhabitants) which includes other towns

like South Shields and Sunderland.

The Tyne and Wear network is a metro-like light rail system, using

newly built track and coverted main lines. The

river Tyne is crossed on a new bridge. There are also short tunnels

between Tynemouth and North Shields and between Chillingham Road

and Byker. Some grade crossings excist along the branch to the

Airport and one at Howdon on the route to Tynemouth. The new Sunderland

Line shares tracks with main line services.

The

system is operated by Nexus: the Tyne and Wear Passenger Transport

Executive, which also administers funds on behalf of the Tyne

and Wear Passenger Transport Authority. Patronage has been declined

due to bus deregulation during the eighties. Recently patronage

is improved. However, the use during the first months of its operation

of the Sunderland extension seems to be disappointing.

Extension Sunderland

Extension Sunderland

Source:

LRTA (Iain D.O. Frew, 11 April 2002)

The

extension of the Tyne and Wear metro from Pelaw over Railtrack's

metals to Sunderland and thence over the relaid line to South

Hylton duly opened on Easter Day 31 March 2002. Park Lane station,

under Sunderland's bus station was not sufficiently complete and

will not open until 28 April, but everything else was ready. At

many of the stations the fitting out with metro furnishings was

not quite complete and many lack the laminated panels for the

walls of shelters, but this did not prevent the stations opening

for the new service. Nexus must be commended for how completely

they have resigned the entire system to include mention of Sunderland

and South Hylton on direction boards etc.

The

new service operates approximately every ten minutes - there are

slight variations due to the times of Railtrack workings. Services

comprise two articulated metrocars and this represents a considerable

increase in capacity over the former service. Arriva still run

a half hourly fast service from Central Station to Sunderland

and thence to Hartlepool or Teesside. The bi-hourly Transpennine

service from Liverpool to Sunderland that was to be cut back to

Newcastle continues to run though loads are light. The Metro service

replaces Arriva's half hourly locals.

The

volume of traffic originating at Sunderland is already much higher

than that generated by the former service. The eastern of the

two old island platforms has been widened and is used by all trains.

The northern end is used by Arriva and the southern end by Nexus.

A new entrance with a lift has been built at the northern end

which means that the substantial pram traffic attracted by the

Metro is at the wrong end of the station for the lift. Being totally

covered over the station is inevitably something of a dark hole

and a great deal more is needed to make it in any way attractive.

Fellgate, the first new stop east from Pelaw, is an immediate

success with steady traffic all day long. St Peter's in contrast

is extremely quiet so far - perhaps BR's decision years ago to

close adjacent Monwearmouth was justifiable after all! On the

reopened section of the Durham branch, University is building

up useful traffic and South Hylton is surprisingly busy. A nearby

school is producing substantial traffic. Pallion is quite busy

at peak hours but is quiet so far off peak.

The

South Hylton services are already overcrowded significantly at

busy times - not just the rush hour - and the question of three

car trains is already being mentioned. The platforms at all of

the new stations can be lengthened to take three cars easily,

as can all the stations on the pre-existing parts of the system.

The extension is off to a great start and there is so much potential

for further growth when new car parks become fully used, and communities

rediscover a convenient frequent service on their doorsteps

The future of public transport in Tyne

and Wear starts here

The future of public transport in Tyne

and Wear starts here

Source:

NEXUS (25/07/02)

THE

Tyne and Wear Passenger Transport Authority has ratified a visionary

plan for the future of public transport in Tyne and Wear. Called

“Towards 2016”, the plan is the culmination of extensive

consultation on the future of public transport in Tyne and Wear

by public transport operators Nexus. The

opinions of local authorities, operators, passengers and the public

have been taken into account when compiling the document. And

there is widespread support for the plans which will bring 50

per cent of Tyne and Wear residents within reach of high quality

public transport.

Some

routes will be served by street-running trams which operate on

Metro tracks and some routes may be served by advanced bus systems.

Technical, financial and operational experts are now examining

the proposals in detail with a view to implementing the schemes

contained within the document.

Equally

welcomed are plans to make public transport easier to use, and

to provide flexible services that operate at times and to places

that are determined by passengers. An

extended commuter rail network will provide access to jobs for

people who live in Tyne and Wear and in neighbouring areas.

Mike

Parker, Director General of Nexus, said: “This report

heralds a new era in public transport provision. As congestion

grows the quality and capacity provided by public transport needs

to undergo a step change. The

next 15 years will see major projects such as Orpheus rally over

the mantle of the Metro, a major transformation of the speed and

reliability of our main bus services and new technologies in ticketing

and information which will reduce the need for cars for many journeys.”

Danny

Marshall, Chairman of the Tyne and Wear Passenger Transport Authority,

said: “I am delighted that this major plan has the support

of our five local authorities. We

all recognise that the ‘do nothing’ scenario is not

an option. “I will be working with my colleagues in the District

Councils in Tyne and Wear to ensure we have a coherent countywide

approach to transport issues such as parking and traffic management

to promote public transport as a more attractive option.”

Network

Network

Yellow line: Newcastle/centre-Tynemouth-Newcastle/centre-Pelaw.

Yellow line: Newcastle/centre-Tynemouth-Newcastle/centre-Pelaw.

Green line:

Airport-Newcastle/centre-South Shields, -Sunderland.

Green line:

Airport-Newcastle/centre-South Shields, -Sunderland.

Data

Data

Opened: between 1980 and 1984, the first of the new metro style

systems outside London. Cost of construction: £284 million

(outturn prices). Mostly new railway construction under central

Newcastle and over the Tyne, with some use of former rail alignments.

An extension to Newcastle Airport opened in 1991, and to Sunderland

in early 2002 (partly track sharing).

Opened: between 1980 and 1984, the first of the new metro style

systems outside London. Cost of construction: £284 million

(outturn prices). Mostly new railway construction under central

Newcastle and over the Tyne, with some use of former rail alignments.

An extension to Newcastle Airport opened in 1991, and to Sunderland

in early 2002 (partly track sharing).

Operator:

Nexus, the Tyne & Wear PTE.

Operator:

Nexus, the Tyne & Wear PTE.

Number of

stations: 58

Number of

stations: 58

Length of

route: 77 km

Length of

route: 77 km

Staff: 606

Staff: 606

Fleet: 90

passenger cars, all wheelchair accessible.

Fleet: 90

passenger cars, all wheelchair accessible.

Power supply

1.5KV DC overhead line.

Power supply

1.5KV DC overhead line.

Segregated

metro style system with some stations underground, and some grade

crossings.

Segregated

metro style system with some stations underground, and some grade

crossings.

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 229.2 million

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 229.2 million

Passenger

journeys 2000/01: 33 million

Passenger

journeys 2000/01: 33 million

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £24 million

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £24 million

Future expansion:

“Towards 2016” (street-running trams, which operate

on Metro tracks, and quality bus corridors).

Future expansion:

“Towards 2016” (street-running trams, which operate

on Metro tracks, and quality bus corridors).

7.

Sheffield

(Supertram),

or back to: [intro] [menu]

Is it really super?

Is it really super?

The

agglomeration of South Yorkshire centred around Sheffield became

the second urban region in Britain to reintroduce street-running

light rail in 1994. Unlike Manchester's Metrolink which connected

two existing suburban rail lines, Sheffield's 29 km Supertram

system was developed from scratch, largely without using existing

rail infrastructure and involving a high share of on-street alignments,

making up over half of

the network.

Photo: (C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Sheffield, Middlewood, March 14, 2002

Also,

construction and initial operation of the system was carried out

by a subsidiary of the publicly-owned regional agency South Yorkshire

assenger Transport Executive (SYPTE) and only privatised (as planned)

in 1998, four years after opening.

Funding of the Supertram derived largely from a central government

grant and regional loans (in equal parts), while local businesses,

most prominently a large shopping centre at one of the five branch

termini, also contributed a minor amount.

More than in most new light rail cities, Sheffield's Supertram

faced an uphill battle among policymakers, the general public,

the media and not least the competitive public transport environment.

While planning authorities had, after years of studies and debates,

gained approval and funding for Supertram as the preferred option

to alleviate the traffic stranglehold and CBD decline Sheffield

was experiencing, the high level of

disruption to businesses and traffic along the routes during construction

appears to have dimmed public enthusiasm about the project even

before inauguration.

Other than Manchester's Metrolink which could bank on existing

patronage from the heavy rail lines it took over, Sheffield's

Supertram had no influence on the kind and level of services bus

providers would continue to offer in its corridors and thus started

virtually from zero. A number of teething problems had to be overcome,

such as the regulation of traffic along the on-street alignments

which had initially caused trams to be caught up in congestion,

or the procedures for ticketing and cooperation with other carriers

(after stationary ticket machines had become prone to vandalism,

Supertram resorted to the introduction of on-board conductors

which seems to have resulted in a not insignificant ridership

boost). While all indications are that the CBD has gained economically

with retail sales and building occupancy rates up, revitalisation

of other areas along Supertram's corridors appears to be slow

and not obviously higher than in parts of Sheffield not served

by the system. Above all, the development of ridership has been

below expectations for the first few years, though latest figures

(post-1996) look more optimistic.

Photo:

(C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Sheffield, centre & Halfway, March 14, 2002

Not

surprisingly, the unfavourable first years of Supertram put an

enormous financial strain on the operator, then still controlled

by SYPTE. Unbacked running costs and non-trading credits had caused

financial liabilities to SYPTE amounting to £115m in early

1998. The agency lost a court case against national government

who had wrongly been perceived as contractually tied to bridging

this gap. The debt burden resulted in a rather symbolic sale value

of £1.5m when Supertram's operations were privatised in

that year; the context was the likelihood of council tax increases

which would have worked further against the public image of Supertram

and possibly of light rail schemes in Britain in general (Harding

1998).

However,

since 1998 much has been improved! Supertram is used very well

during the last few years. This Light rail is reallly super,

as a local newspaper stated. Parts of the infrastructure is or

will be improved. Extensions has been planned.

Network

Network

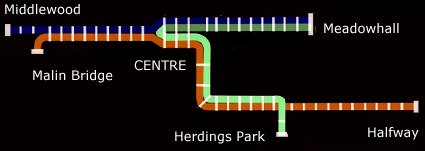

Middlewood-centre-Meadowhall

Middlewood-centre-Meadowhall

Malin Bridge-centre-Halway

Malin Bridge-centre-Halway

An extra service operates between 9 am and 6 pm from Meadhall

to Herdings Park via centre. This third line shuttles between

3 stops in the centre. Trams from Meadowhall turns at Cathedral

for direction Herdings Park (and vice versa).

Data

Data

Opened: 1994/95.

Cost of construction: £240 million. On-street running tramway

with some segregation from other traffic.

Opened: 1994/95.

Cost of construction: £240 million. On-street running tramway

with some segregation from other traffic.

Operator:

Stagecoach Holdings (from 1997). Owned by South Yorkshire Passenger

Transport Executive.

Operator:

Stagecoach Holdings (from 1997). Owned by South Yorkshire Passenger

Transport Executive.

Number of

tram stops: 47, step-free access, wheelchair accessible.

Number of

tram stops: 47, step-free access, wheelchair accessible.

Length of

route: 29 km

Length of

route: 29 km

Staff: 250

Staff: 250

Fleet: 25

passenger cars of low floor design, all wheelchair accessible.

Fleet: 25

passenger cars of low floor design, all wheelchair accessible.

Power supply

750V DC overhead line.

Power supply

750V DC overhead line.

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 38 million

Passenger

kilometres 2000/01: 38 million

Passenger

journeys 2000/01: 11 million

Passenger

journeys 2000/01: 11 million

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £7 million

Passenger

receipts 2000/01: £7 million

Future expansion

plans: route extensions are being considered.

Future expansion

plans: route extensions are being considered.

8.

Future

projects,

or back to: [intro] [menu]

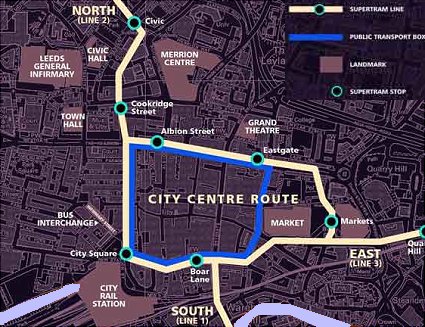

Leeds

Centre Loop of the new 3-line system

Approval

was granted in March 2001 for the £487 million Leeds Supertram

and the £190 million South Hampshire Rapid Transit, both

of which are currently at the tendering stage and are due for

completion in 2006. Three extensions to Manchester Metrolink are

also at the tendering stage. New systems are also planned for

Bristol (£194m) and Merseyside (£215m). Transport

for London is considering four rapid transit schemes in the capital,

using either guided buses or trams. A number of other schemes

are under consideration or are being developed by local authorities.

9.

Blackpool

and more,

or back to: [intro] [menu]

Balloons and doubledecks

Balloons and doubledecks

Blackpool is the only 'Victorian' tramway which survived the

destruction of UK's trams in the pre- and post-war period of the

last century. Still doubledeck trams run along the boulevard.

Some of them are called 'balloons'.

In the near future this old tramway will possibly be converted

to a real light rail system.

Photo: (C) Light

Rail Atlas/Rob van der Bijl

Ballooncar at boulevard

Blackpool, summer 1978

More...

More...

All

other tramways in the UK are heritage, museum, or tourist systems

(such as Beamish, Crich and Seaton).